Taking the Tablets on the S & D

I grew up in the 40s 50s and 60s in Dorset's smallest town, Stalbridge, in the far north of the county, just half a mile south of the Somerset border, and my first memories of trains began here.

Located in the heart of the rich agricultural lands of the Blackmore Vale, (yes, SR Bullied Pacific locomotive, 21C123 'Blackmoor Vale' is miss-spelt !), Stalbridge was a typical rural community with no particular claim to fame, except that for several years in the 17th century the local Lord of the Manor was the celebrated scientist Robert Boyle. He carried out much of his early experimental work on gases in a purpose-built laboratory within the Manor House. This work, of course, culminated in the well-known 'Boyle's Law'.

This rural backwater changed somewhat in 1863 with the coming of the Dorset Central Railway, and the building of a local station. After a few years, of course, the Dorset Central, through merger with the Somerset Central, was to become part of the fabled Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway (the 'S&D'), and Stalbridge was on the main line from Bath to Bournemouth, just 3.4 miles south of Templecombe.

As with many communities with the coming of the railways, Stalbridge started to attract local businesses, and before motorised road transport, the station became commercially important serving a local gasworks, large timber mill, milk factory, glove factory, a cattle market, as well as the main Post Office serving a large area.

Much has been said and written about the nature and workings of the S&D and its locomotives, no further narrative is necessary here, emphasis will be on the unusual means of train control token exchange.

The main line between Bath and Bournemouth alternated 3 times between single and double-line working on its 71 mile route. This, of course necessitated the use of some sort of token system to protect trains on the single-line sections.

In 1886, the company installed Tyer's system of 'Electric Train Tablets' to control the signalling and point work, using interlocking instruments into which the tablets fitted, in each signal box. The tablets themselves were gunmetal discs, approximately 4 ins in diameter, and each disc contained a unique pattern of notches so it could be used like a key, exclusively on its own section of line or 'block'. Each single-line section was divided into blocks some 3 to 8 miles in length, each block being protected by its own unique tablet, which were exchanged at the various 'block-posts' along the line.

The basic idea is that the tablet acts as a "key" to unlock the signals and points at each end of the block, and any train entering the block must carry it to the block-post at the other end. Since there was only one tablet for each block, this ensured that (provided all signals were obeyed), only one train could be in the block at any one time, and thus avoided the nightmare scenario of head-on collisions.

On the southbound journey, the second single line section began at Templecombe, and Stalbridge was the first block-post at which there was a full exchange of 2 tablets. For transportation between block-posts the tablets themselves were protected in a stout leather pouch with a steel loop carrying handle.

Located in the heart of the rich agricultural lands of the Blackmore Vale, (yes, SR Bullied Pacific locomotive, 21C123 'Blackmoor Vale' is miss-spelt !), Stalbridge was a typical rural community with no particular claim to fame, except that for several years in the 17th century the local Lord of the Manor was the celebrated scientist Robert Boyle. He carried out much of his early experimental work on gases in a purpose-built laboratory within the Manor House. This work, of course, culminated in the well-known 'Boyle's Law'.

This rural backwater changed somewhat in 1863 with the coming of the Dorset Central Railway, and the building of a local station. After a few years, of course, the Dorset Central, through merger with the Somerset Central, was to become part of the fabled Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway (the 'S&D'), and Stalbridge was on the main line from Bath to Bournemouth, just 3.4 miles south of Templecombe.

As with many communities with the coming of the railways, Stalbridge started to attract local businesses, and before motorised road transport, the station became commercially important serving a local gasworks, large timber mill, milk factory, glove factory, a cattle market, as well as the main Post Office serving a large area.

Much has been said and written about the nature and workings of the S&D and its locomotives, no further narrative is necessary here, emphasis will be on the unusual means of train control token exchange.

The main line between Bath and Bournemouth alternated 3 times between single and double-line working on its 71 mile route. This, of course necessitated the use of some sort of token system to protect trains on the single-line sections.

In 1886, the company installed Tyer's system of 'Electric Train Tablets' to control the signalling and point work, using interlocking instruments into which the tablets fitted, in each signal box. The tablets themselves were gunmetal discs, approximately 4 ins in diameter, and each disc contained a unique pattern of notches so it could be used like a key, exclusively on its own section of line or 'block'. Each single-line section was divided into blocks some 3 to 8 miles in length, each block being protected by its own unique tablet, which were exchanged at the various 'block-posts' along the line.

The basic idea is that the tablet acts as a "key" to unlock the signals and points at each end of the block, and any train entering the block must carry it to the block-post at the other end. Since there was only one tablet for each block, this ensured that (provided all signals were obeyed), only one train could be in the block at any one time, and thus avoided the nightmare scenario of head-on collisions.

On the southbound journey, the second single line section began at Templecombe, and Stalbridge was the first block-post at which there was a full exchange of 2 tablets. For transportation between block-posts the tablets themselves were protected in a stout leather pouch with a steel loop carrying handle.

A selection of typical tablets from the Southern half of the line showing the unique pattern of notches in each tablet

Photo: Chris Hughes

Photo: Chris Hughes

The system worked well, but it was time consuming, as trains had to slow down or stop to exchange tablets. By the turn of the century, the S&D Locomotive Superintendent, Alfred Whitaker, was determined to cut journey times by improving the tablet exchange procedure. In 1905 he patented his 'Whitaker Apparatus' which enabled tablets to be exchanged with moving trains travelling at up to 60 mph. The new apparatus actually reduced journey times between Bath and Bournemouth by a full 10 minutes.

Mechanically the system was fairly simple. The lineside apparatus consisted of a cast iron pedestal supporting a vertical shaft to which was attached a horizontal arm that could be swung out 90 degrees from its 'rest' position parallel with the line. The swinging arm carried either one or two brackets for the tablet pouches.

Exchanges within each block required 2 brackets for collection and delivery of the relative tablets. At the end of each single section, of course, only one bracket was required since the train was either collecting the first tablet or giving up the last one for the section.

Mechanically the system was fairly simple. The lineside apparatus consisted of a cast iron pedestal supporting a vertical shaft to which was attached a horizontal arm that could be swung out 90 degrees from its 'rest' position parallel with the line. The swinging arm carried either one or two brackets for the tablet pouches.

Exchanges within each block required 2 brackets for collection and delivery of the relative tablets. At the end of each single section, of course, only one bracket was required since the train was either collecting the first tablet or giving up the last one for the section.

The Up-line tablet exchanger at Stalbridge station, clearly showing the double bracket, with the catcher above and the delivery holder below. Also note the counter-weighted handle and quadrant bevel gear to swing the main arm into the exchange position.

Photo courtesy of Stalbridge Archive Society

Photo courtesy of Stalbridge Archive Society

The collector hook or 'catcher' was on the top bracket, whilst the delivery holder was underneath. A similar arrangement, in reverse, was carried by the locomotive. The equipment was attached to the locomotive, usually low down at the front of the tender, on a sliding or hinged arm. All locomotives from the local engine sheds at Bath, Templecombe, or Branksome, were equipped with Whitaker's apparatus.

Midland 0-6-0 44560 just before the point of exchange, with the tablet pouches clearly visible in both the tender bracket and ground apparatus.

Photo: courtesy of Stalbridge Archive Society

Photo: courtesy of Stalbridge Archive Society

In use, as a train approached, the local signalman would load the ongoing tablet pouch into the lineside holder, and then swing the arm out to the exchange position, using a counter-weighted handle which moved the arm through single-quadrant bevel gears. The loco fireman would similarly load his tablet into the deliverer and push the arm out into position.

After the exchange, the momentum from the arriving tablet was sufficient to push the operating handle past its vertical balance point, so that the counter-weight would gently return the arm to it's safe 'rest' position, the pouch then being removed by the attendant signalman, and returned to the signal box instrument to unlock the signals for the block the train had just left.

Contrary to common belief, the S&D was not the only company to use the Whitaker Apparatus. In 1906 the company licensed its manufacture and use to both the Midland and the Midland and Great Northern Railways, who employed it on some branch lines in Cambridgeshire and East Anglia.

After the exchange, the momentum from the arriving tablet was sufficient to push the operating handle past its vertical balance point, so that the counter-weight would gently return the arm to it's safe 'rest' position, the pouch then being removed by the attendant signalman, and returned to the signal box instrument to unlock the signals for the block the train had just left.

Contrary to common belief, the S&D was not the only company to use the Whitaker Apparatus. In 1906 the company licensed its manufacture and use to both the Midland and the Midland and Great Northern Railways, who employed it on some branch lines in Cambridgeshire and East Anglia.

Action shot just after the moment of exchange with the tablet pouches still swinging from the momentum imparted at impact. The bracket arm would then gently swing back to the 'rest' position under the weight of the counter-balanced handle.

Photo: courtesy of Stalbridge Archive Society

Photo: courtesy of Stalbridge Archive Society

As a small boy, I can vividly remember being totally fascinated watching this exciting procedure when my mother used to take me down to the level crossing to watch the Pines Express pass by. Our viewpoint was only about 10 feet from the up-line exchanger so we had a front-seat view for all the action.

The view from Stalbridge signal box with a Northbound 'Pines Express' approaching the awaiting tablet in the exchanger. The gate in the right foreground is where the author regularly stood as a small boy to watch the action.

Photo: courtesy of Stalbridge Archive Society

Photo: courtesy of Stalbridge Archive Society

Despite subsequent studies by both the Southern Railway and BR, the Whitaker Apparatus was never replaced, and was in constant use for some 60 years till line closure in 1966. Only in the last couple of years, as many 'foreign' locomotives without catchers were drafted in, was manual tablet exchange occasionally used again.

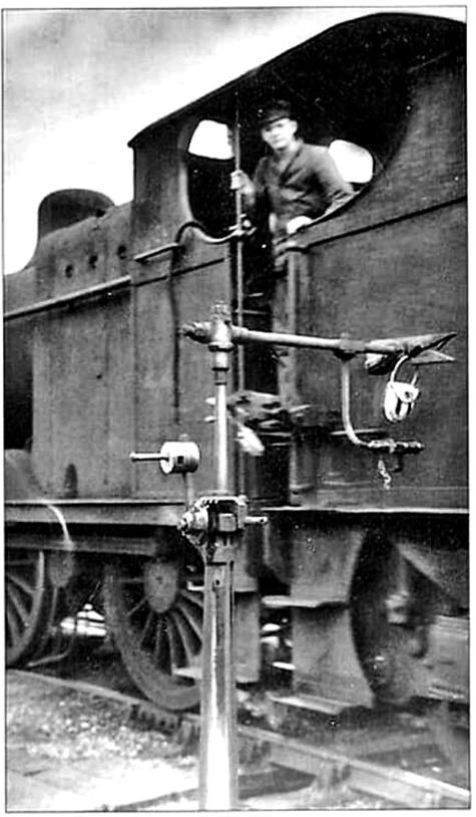

In the final months before closure, when many outside locomotives without catchers were drafted in, tablet exchange

was often achieved by less conventional means, as demonstrated here by Alan Cox, Stalbridge's last signalman.

Photo courtesy of Stalbridge Archive Society

was often achieved by less conventional means, as demonstrated here by Alan Cox, Stalbridge's last signalman.

Photo courtesy of Stalbridge Archive Society

Chris Hughes (April 2024)