By Ernie Wilson

Chapter One - Early Days

I was born on 29th May 1920 at Newburn in Northumberland, the youngest of eight children. Times were very hard after four years of war. My father made steel for John Spenser & Sons and was an expert at his job. He told me that he had made a steel called ‘Double - Bullet' which they had to send to Birmingham to shear, He worked with his men and could lift a one hundred weight pot from the furnace with a pair of tongs and pour steel into a mould.

He had pneumonia and bronchitis three times, was given up twice but survived. Mother used to keep salt bags in the oven and change them in his bed at regular intervals. She also put the ironing irons in front of the fire on the stand my Dad had made at the steel works, then she ironed his back over brown paper.

Mother worked like a slave, making bread twice a week and doing all our washing with soda, soap and a scrubbing brush, our shirts and clothes were always immaculate. George, my favourite brother, and I turned the rollers on our big mangle every Wednesday. It took a whole day to do the washing. Three pit chimneys belched out smoke and the clothes, of course, got covered in smuts. Mother knew how to cope and turned us all out Sunday with clean white shirts and clean dresses for church.

My friend John Tait, Johnty we all called him, my best friend, was very poor. His father had no work and could not afford to buy him boots for school, so he always went to school with bare feet. He was a good footballer and I shall never know how he stood the pain of kicking a football, but he was chosen to play for the District Team. My sister Petena gave him a pair of her shoes with 'Cuban' heels - that was the fashion then. Johnty fastened them to his feet with bandages and played a cracking game.

Of course we always followed our hero Jack Allan who lived at the top of our street (Westmacott Street). They had a sweet shop and his father used to sell vegetables from a horse and cart. He used to stop at the recreation ground on Saturday evenings and played in goal for us to practice. He would give us a halfpenny every time we scored, which wasn’t very often. I have never seen a man with bigger hands. He could pick a size five football up with one hand and throw it to the halfway line. Of course his son Jack came back to Newcastle with the F.A. Cup in 1932. My eldest brother Robert took me to the Central Station in Newcastle to see the team come back with the Cup.

Chapter One - Early Days

I was born on 29th May 1920 at Newburn in Northumberland, the youngest of eight children. Times were very hard after four years of war. My father made steel for John Spenser & Sons and was an expert at his job. He told me that he had made a steel called ‘Double - Bullet' which they had to send to Birmingham to shear, He worked with his men and could lift a one hundred weight pot from the furnace with a pair of tongs and pour steel into a mould.

He had pneumonia and bronchitis three times, was given up twice but survived. Mother used to keep salt bags in the oven and change them in his bed at regular intervals. She also put the ironing irons in front of the fire on the stand my Dad had made at the steel works, then she ironed his back over brown paper.

Mother worked like a slave, making bread twice a week and doing all our washing with soda, soap and a scrubbing brush, our shirts and clothes were always immaculate. George, my favourite brother, and I turned the rollers on our big mangle every Wednesday. It took a whole day to do the washing. Three pit chimneys belched out smoke and the clothes, of course, got covered in smuts. Mother knew how to cope and turned us all out Sunday with clean white shirts and clean dresses for church.

My friend John Tait, Johnty we all called him, my best friend, was very poor. His father had no work and could not afford to buy him boots for school, so he always went to school with bare feet. He was a good footballer and I shall never know how he stood the pain of kicking a football, but he was chosen to play for the District Team. My sister Petena gave him a pair of her shoes with 'Cuban' heels - that was the fashion then. Johnty fastened them to his feet with bandages and played a cracking game.

Of course we always followed our hero Jack Allan who lived at the top of our street (Westmacott Street). They had a sweet shop and his father used to sell vegetables from a horse and cart. He used to stop at the recreation ground on Saturday evenings and played in goal for us to practice. He would give us a halfpenny every time we scored, which wasn’t very often. I have never seen a man with bigger hands. He could pick a size five football up with one hand and throw it to the halfway line. Of course his son Jack came back to Newcastle with the F.A. Cup in 1932. My eldest brother Robert took me to the Central Station in Newcastle to see the team come back with the Cup.

They were on the upper deck of an open tramcar. I was sitting on my eldest brother Robert’s shoulders (he was a miner) and the crowds were so dense that he could not put me down. He was exhausted by the time we managed to get out of the crowd. Robert was my brother who took me to St. James's Park on Saturday afternoons when Macinroy played in goal and Sammy Weaver was on the right wing. My brother George had no interest in sport but loved motor bikes. We used to spend hours together trying to get his old motorbike to start, then he would take me on the pillion. We went all over the countryside. He also liked messing about with electrics. I remember one time when he was mending a switch in the back kitchen he put his screwdriver on the live wire and caught hold of my ear. It was as I imagined like the Electric Chair. My mother gave him a hiding but we were still good friends. He also taught me to ride a bike. Of course we lived on a steep hill and streets were all covered with big stones. He put me on the saddle and ran with me down the hill until he could run no faster and had to let me go. My hands were not big enough to reach the brakes and I crashed into a telegraph pole, making my nose bleed, also my knees. I was warned not to tell Mother what had happened.

I started school wearing a yellow knitted hat. All the boys shouted at me 'Lassie Lassie Rhubarb'. I was like the boy called ‘Sue’. I had to prove myself. These days it is the fashion, then it was like being a pansy. I loved my school for all the running and football but hated history or should I say my history teacher. I could only remember 1066 ‘The Battle of Hastings’. After that I was beat.

I was caught smoking in the toilets during playtime, this was on a Friday. The Headmaster took my cigarette case from me, which was full of cigarette cards covering two woodbines which were five cigarettes for two pence. Johnty and I used to buy a packet between us and share them. I had forgotten all about this encounter when I went into Assembly on the following Monday morning (with the girls who were next door). After prayers the Head Master, Mr. Beale, said that he had caught a boy smoking the previous Friday and called me out to receive my punishment, three strokes on each hand, and then over the desk. Some of the girls were crying but I gritted my teeth and took my punishment without a tear.

Mr. Walker, my favourite teacher, allowed me to do silent reading for the next two days as I could not write - my hands were swollen. I lied to my Mother when trying to use a knife and fork to eat my dinner. I told her that I had fallen in the playground, that saved me from getting another hiding for smoking.

I joined the Newburn Church Choir at the age of eight, and used to sing for funerals when asked to do so by the bereaved. They used to ask for me or two other boys who were head chiorboys. We used to be paid for this and of course missed lessons. Once I sang in Durham Cathedral 'O for the Wings of a Dove’.

I started school wearing a yellow knitted hat. All the boys shouted at me 'Lassie Lassie Rhubarb'. I was like the boy called ‘Sue’. I had to prove myself. These days it is the fashion, then it was like being a pansy. I loved my school for all the running and football but hated history or should I say my history teacher. I could only remember 1066 ‘The Battle of Hastings’. After that I was beat.

I was caught smoking in the toilets during playtime, this was on a Friday. The Headmaster took my cigarette case from me, which was full of cigarette cards covering two woodbines which were five cigarettes for two pence. Johnty and I used to buy a packet between us and share them. I had forgotten all about this encounter when I went into Assembly on the following Monday morning (with the girls who were next door). After prayers the Head Master, Mr. Beale, said that he had caught a boy smoking the previous Friday and called me out to receive my punishment, three strokes on each hand, and then over the desk. Some of the girls were crying but I gritted my teeth and took my punishment without a tear.

Mr. Walker, my favourite teacher, allowed me to do silent reading for the next two days as I could not write - my hands were swollen. I lied to my Mother when trying to use a knife and fork to eat my dinner. I told her that I had fallen in the playground, that saved me from getting another hiding for smoking.

I joined the Newburn Church Choir at the age of eight, and used to sing for funerals when asked to do so by the bereaved. They used to ask for me or two other boys who were head chiorboys. We used to be paid for this and of course missed lessons. Once I sang in Durham Cathedral 'O for the Wings of a Dove’.

My Mother was a good Christian and had to be very ill to miss church on Sunday. I had to go about four times, even when my voice broke and I started work. I used to work in a grocer's shop, learning the trade.

We use to close at 9pm on a Saturday night. By the time we cleared the shop it was 10pm. Then the girls scrubbed the counters and I, the apprentice, had to scrub the stone floor.

The manageress and the head counter man took'stock of all the perishable fats etc and all the eggs had to be counted, thirty hands to a box, (six to a hand). When I worked at the Gateshead Shop I used to run over the Redheugh Bridge to get to Newcastle to get the last train to Newburn. I often missed this and had to go to the bus station to catch the Miners’ Bus which arrived home at five minutes to midnight. Mother used to call me on Sunday morning to serve at Church for 6am Holy Communion. Several times I fainted but still had to carry on. This turned me against religion and I began to think for myself - this was not necessary to be a good person.

I was earning seven shillings and sixpence a week, Mother used to give me one - and - six pocket money. I bought an egg case for six pence from the Meadow Dairy and chopped it up for sticks. These I put into bundles and sold for 2d a bundle, making about 2s. 6d profit. My friend Johnty started serving his apprenticeship at Vickers - Armstrong as a fitter and turner. He was always in trouble. He was turning the job one-day and left the drill running, instead of turning the power off. He lost a lock of his curly hair and part of his scalp. We brought a trilby hat between us and wore it on alternative nights. We throught we were the Cat's Whiskers!

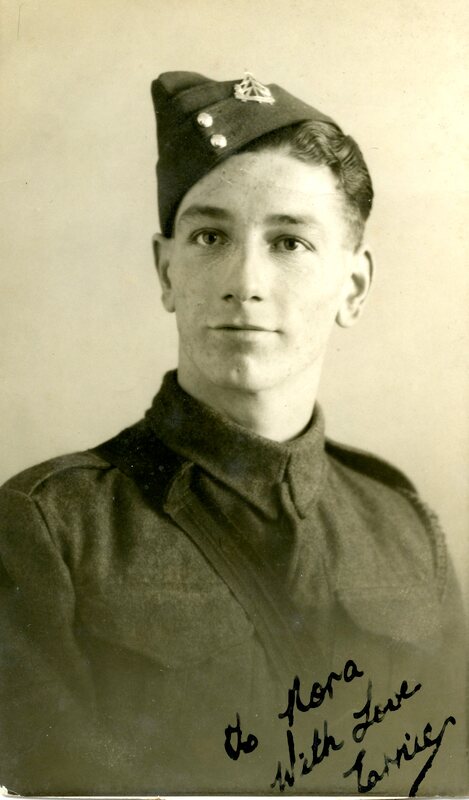

1939 and war was imminent. What should we do? Whatever we were going to do we would do it together. I wanted to join the Navy as it was clean and no square bashing or carrying packs etc. Johnty wanted to join the Army, so we spun the coin and Johnty won. I went into the Drill Hall at Newburn to join the local territorials. I had my medical and tests, which I passed ok. I waited in the room for Johnty but when he came out he said that he had failed his medical as he had a TB knee when at school, so I was on my own and Johnty was still working at Vickers - Armstrong.

We use to close at 9pm on a Saturday night. By the time we cleared the shop it was 10pm. Then the girls scrubbed the counters and I, the apprentice, had to scrub the stone floor.

The manageress and the head counter man took'stock of all the perishable fats etc and all the eggs had to be counted, thirty hands to a box, (six to a hand). When I worked at the Gateshead Shop I used to run over the Redheugh Bridge to get to Newcastle to get the last train to Newburn. I often missed this and had to go to the bus station to catch the Miners’ Bus which arrived home at five minutes to midnight. Mother used to call me on Sunday morning to serve at Church for 6am Holy Communion. Several times I fainted but still had to carry on. This turned me against religion and I began to think for myself - this was not necessary to be a good person.

I was earning seven shillings and sixpence a week, Mother used to give me one - and - six pocket money. I bought an egg case for six pence from the Meadow Dairy and chopped it up for sticks. These I put into bundles and sold for 2d a bundle, making about 2s. 6d profit. My friend Johnty started serving his apprenticeship at Vickers - Armstrong as a fitter and turner. He was always in trouble. He was turning the job one-day and left the drill running, instead of turning the power off. He lost a lock of his curly hair and part of his scalp. We brought a trilby hat between us and wore it on alternative nights. We throught we were the Cat's Whiskers!

1939 and war was imminent. What should we do? Whatever we were going to do we would do it together. I wanted to join the Navy as it was clean and no square bashing or carrying packs etc. Johnty wanted to join the Army, so we spun the coin and Johnty won. I went into the Drill Hall at Newburn to join the local territorials. I had my medical and tests, which I passed ok. I waited in the room for Johnty but when he came out he said that he had failed his medical as he had a TB knee when at school, so I was on my own and Johnty was still working at Vickers - Armstrong.

Chapter Two

To France and Back

To France and Back

On the Sunday morning when war broke out I was standing on parade in the Newburn School yard, which I had attended as boy. My sisters were looking at the parade when a solider with a motor cycle and sidecar turned up and wanted me to go to Prudhoe Drill Hall where they issued clothing etc to the new recruits. When I was whisked away my family thought I was going to France right away, there was much crying and worry.

I went to France with 2nd / 4th Northumberland Fusiliers, this was a motor cycle battalion known as the 8th Btn Northumberland Fusiliers, commanded by Major Gaskell. We sailed from Southampton on St. George’s Day and, as he was our Patron Saint, we wore our Red Rose in our Glengarry. We landed at Cherbourg as green as green. Our biggest weapon was a 2 lbs Boys Anti-Tank rifle, this was no match for Hitler's Tanks and Armoured vehicles. After our first inspection in France, the Duty Officer asked me if I had shaved in the morning. ‘No Sir’ I replied. ‘I don’t shave'. ‘Then you b----- well start tonight at 6pm and parade with

the guard for seven days, and shave every day whether you need one or not’. This I still do.

We moved forward up into Belgium, just in time for the Belgians to pack up, so we had to make a speedy withdrawal back to Arras in France, or be taken prisoner. Arras had been heavily bombed and a huge crater was in the centre of the town. No vehicles could come in and those which were in could not get out, except of course the Northumberland Fusiliers who could ride motor cycles and side cars. We used to lift the sidecars and ride on two wheels. Tommy Clark was our Transport Sgt. and I wrote a poem about him while getting a hammering from the Stukas Dive Bombers. It goes something like this;

‘The Sgt. of our Transport His second name is Clark With him and his mechanics We often play a lark.

I went to France with 2nd / 4th Northumberland Fusiliers, this was a motor cycle battalion known as the 8th Btn Northumberland Fusiliers, commanded by Major Gaskell. We sailed from Southampton on St. George’s Day and, as he was our Patron Saint, we wore our Red Rose in our Glengarry. We landed at Cherbourg as green as green. Our biggest weapon was a 2 lbs Boys Anti-Tank rifle, this was no match for Hitler's Tanks and Armoured vehicles. After our first inspection in France, the Duty Officer asked me if I had shaved in the morning. ‘No Sir’ I replied. ‘I don’t shave'. ‘Then you b----- well start tonight at 6pm and parade with

the guard for seven days, and shave every day whether you need one or not’. This I still do.

We moved forward up into Belgium, just in time for the Belgians to pack up, so we had to make a speedy withdrawal back to Arras in France, or be taken prisoner. Arras had been heavily bombed and a huge crater was in the centre of the town. No vehicles could come in and those which were in could not get out, except of course the Northumberland Fusiliers who could ride motor cycles and side cars. We used to lift the sidecars and ride on two wheels. Tommy Clark was our Transport Sgt. and I wrote a poem about him while getting a hammering from the Stukas Dive Bombers. It goes something like this;

‘The Sgt. of our Transport His second name is Clark With him and his mechanics We often play a lark.

Now he is quite a decent chap

And that the lads know well

And when to us he does command

We travel like a shell.

In France he travelled in advance

Now that's a risky job

And even though the Gerries came

He never lost his bob.

He flew about upon his bike

Through shell and bomb and bullet

And even though the houses fell

He still kept riding through it’.

And that the lads know well

And when to us he does command

We travel like a shell.

In France he travelled in advance

Now that's a risky job

And even though the Gerries came

He never lost his bob.

He flew about upon his bike

Through shell and bomb and bullet

And even though the houses fell

He still kept riding through it’.

These were tough days, no food, no water and nothing to fight with. One person ‘Snakey Cardwell’ as we called him, carried a German machine gun. He was a Sergeant, he sat on the roof of our billet with his cushion to rest the gun on his shoulder and we passed ammunition through the sky light. He used to shout at the Gerries 'I am too wicked to kill’. He was awarded the Military Metal. He later married a girl from Hinton St. Mary in Dorset, as I did.

We were relieved at Arras, after blowing up all our belongings and ammo, by the Welch Fusiliers, the only bayonet charge I have ever seen. We crept out at dawn on a foggy morning after a gap had been made. We were very wet and hungry. I was with an old soldier ROMS Bob Cowans. He told me to stay with him and I would be all right. I clung to him like a leech. We made our way to Dunkirk but that was only after running, hiding, taking cover and pushing along with the refugees. No one knew who was which. Lieut. Wilson helped us in the night by blowing a bugle just a few toots.

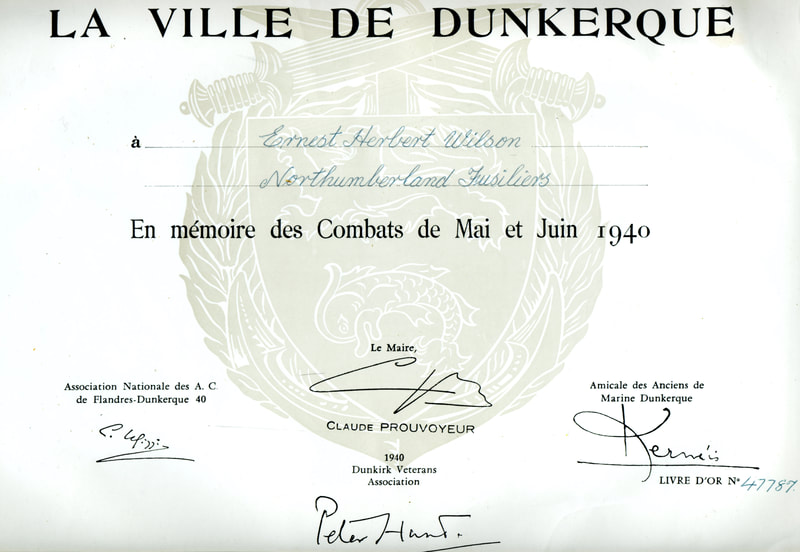

Hungry, with no food or water, we arrived at Dunkirk on my 20th birthday. Eddie Appleby from Westerhope and another four mates celebrated with a tin of sardines and one packet of hard - tack (biscuits). This was terrible, we thought we would be taken off the beach straight away, but it was not to be. Thousands had arrived first so we took cover from the Stukas as best as possible. We carried stretchers on to the hospital ships moored at the broken pier, which had been bombed in two places. Planks were placed over the gaps and we swayed as we walked over them with the wounded. Sgt. French from Lemington was one such hero who had his leg blown off, quite near to us. We carried him on board, one of the sailors threw me a tin of fruit (or so I thought). I put this inside my tunic and looked forward sharing it with my friends on 29th May 1940 (my 20th birthday). Five of us found a place of safety under the cliffs and shared a packed of hard tack and my tin of fruit, which turned out to be a tin of PEAS. We were glad of the water as we had not had a drink or food for seven days. We ate the peas and nothing was left.

It was a very cold night and it was impossible to sleep, bombs and machine gun fire kept us awake. When dawn broke we could see fluorescent soldiers lying on the beach glowing in the semi darkness. A bomb had scored a direct hit down the funnel of the ship which was to have taken the Guards to safety and home.

The Stukas were back again, dive bombing and machine gunning. We had to take cover for another day.

We were relieved at Arras, after blowing up all our belongings and ammo, by the Welch Fusiliers, the only bayonet charge I have ever seen. We crept out at dawn on a foggy morning after a gap had been made. We were very wet and hungry. I was with an old soldier ROMS Bob Cowans. He told me to stay with him and I would be all right. I clung to him like a leech. We made our way to Dunkirk but that was only after running, hiding, taking cover and pushing along with the refugees. No one knew who was which. Lieut. Wilson helped us in the night by blowing a bugle just a few toots.

Hungry, with no food or water, we arrived at Dunkirk on my 20th birthday. Eddie Appleby from Westerhope and another four mates celebrated with a tin of sardines and one packet of hard - tack (biscuits). This was terrible, we thought we would be taken off the beach straight away, but it was not to be. Thousands had arrived first so we took cover from the Stukas as best as possible. We carried stretchers on to the hospital ships moored at the broken pier, which had been bombed in two places. Planks were placed over the gaps and we swayed as we walked over them with the wounded. Sgt. French from Lemington was one such hero who had his leg blown off, quite near to us. We carried him on board, one of the sailors threw me a tin of fruit (or so I thought). I put this inside my tunic and looked forward sharing it with my friends on 29th May 1940 (my 20th birthday). Five of us found a place of safety under the cliffs and shared a packed of hard tack and my tin of fruit, which turned out to be a tin of PEAS. We were glad of the water as we had not had a drink or food for seven days. We ate the peas and nothing was left.

It was a very cold night and it was impossible to sleep, bombs and machine gun fire kept us awake. When dawn broke we could see fluorescent soldiers lying on the beach glowing in the semi darkness. A bomb had scored a direct hit down the funnel of the ship which was to have taken the Guards to safety and home.

The Stukas were back again, dive bombing and machine gunning. We had to take cover for another day.

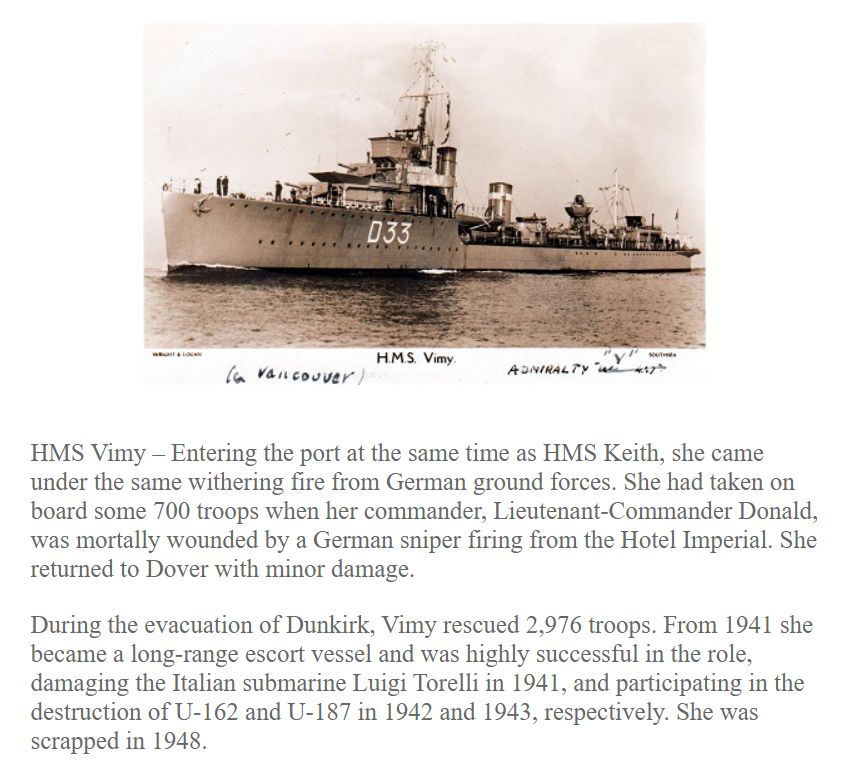

\Ne tried our best to get away from the beach and had a tow from a small vessel but the towrope snapped and we were left at the mercy of anything that may attack us. Fortunately HMS Vimy came to our aid. We were helped on deck but it was so full that we were passed over the shoulders of the packed vessel and pushed down the stairs into the hold. We heard a volley of gunfire and the ship shook. This was the end, but no, it was our guns shooting at the German aircraft. At last we were under way. The sailors gave us hot tea, cheese and bread, the first for nine days. We made pigs of ourselves and ate and drank until we felt ill.

We arrived at Pembroke Docks in Wales, the people on the station offering us food. We had to stay in the train until it was dark, then we formed three ranks and marched up the cobbled hill to Pembroke Barracks. This was heaven to sleep in beds which the local troops had made for us. The next morning I could smell bacon frying and longed to partake, but felt ill after eating all the bread and cheese. I was taken into hospital and put on bread soaks for two days. I didn’t mind this as I could rest and sleep as long as I liked. The next day I was given toast and tea and then I was allowed bacon, eggs and sausages - this was heaven. Woolworths sent us razors, towels etc and we could have baths and regain our pride. I sent a telegram home to Mother 'Arrived safe in England, home soon’. Mother could not believe this as she had been told that I had been ‘killed in action’. This turned out to be a Robert Wilson from Millfield who lived about half a mile from me and also a Northumberland Fusilier.

My eldest sister Annie who had been working with a doctor in Canada was due to travel on the ship coming home to England. This ship was sunk but my sister, who had agreed to carry on work for-another week until a relief was available, came home safely on another ship, the Duchess of Richmond.

I was given leave and arrived in Newcastle at 1am. There was no taxi available so I walked with all my kit the five miles to Newburn. I came down the street in the blackout and knocked on the door. .I heard a voice shout 'Who’s there? Not in a Geordie accent. I thought I was at the wrong house. The door opened and my sister Annie was standing there and we hugged and kissed each other, the frying pan was put on and sausages and eggs were on the go. We talked until the early hours of the morning. Mother couldn’t take all this excitement and was exhausted but happy.

We arrived at Pembroke Docks in Wales, the people on the station offering us food. We had to stay in the train until it was dark, then we formed three ranks and marched up the cobbled hill to Pembroke Barracks. This was heaven to sleep in beds which the local troops had made for us. The next morning I could smell bacon frying and longed to partake, but felt ill after eating all the bread and cheese. I was taken into hospital and put on bread soaks for two days. I didn’t mind this as I could rest and sleep as long as I liked. The next day I was given toast and tea and then I was allowed bacon, eggs and sausages - this was heaven. Woolworths sent us razors, towels etc and we could have baths and regain our pride. I sent a telegram home to Mother 'Arrived safe in England, home soon’. Mother could not believe this as she had been told that I had been ‘killed in action’. This turned out to be a Robert Wilson from Millfield who lived about half a mile from me and also a Northumberland Fusilier.

My eldest sister Annie who had been working with a doctor in Canada was due to travel on the ship coming home to England. This ship was sunk but my sister, who had agreed to carry on work for-another week until a relief was available, came home safely on another ship, the Duchess of Richmond.

I was given leave and arrived in Newcastle at 1am. There was no taxi available so I walked with all my kit the five miles to Newburn. I came down the street in the blackout and knocked on the door. .I heard a voice shout 'Who’s there? Not in a Geordie accent. I thought I was at the wrong house. The door opened and my sister Annie was standing there and we hugged and kissed each other, the frying pan was put on and sausages and eggs were on the go. We talked until the early hours of the morning. Mother couldn’t take all this excitement and was exhausted but happy.

Chapter Three

Training for “D - Day” and Victory.

Training for “D - Day” and Victory.

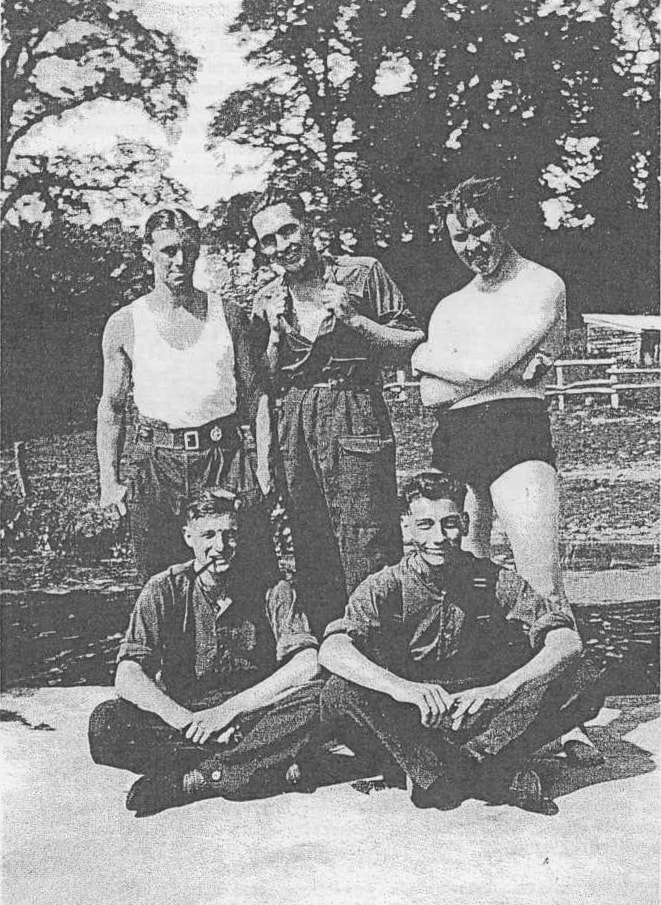

I returned from leave feeling very sad at having to leave home again and reported to Sturminster Newton in Dorset. I had no idea where that was, but was very pleased to find a lovely village. I was billeted at Hinton St. Mary in the hut with twenty drivers. This was my Shangri La, very quiet, until I was awakened by Mr. White bringing in the cows for milking and then the blacksmith banging on his anvil. This is where I met Nora who was the daughter of Reg Innes who had a cycle shop, or should I say ‘curiosity shop’, in the White Hart Yard, Sturminster Newton. I was then made Corporal and moved to the room over the White Hart - the Long Room. I wanted to get away. I couldn’t rest and felt miserable after being home on leave. I met John West, our vehicle mechanic He was also a CpI. in the REME and a first class mechanic. He must have told his mother that I was having my 21st Birthday because she sent me a cheque for £21.00 and a Saffron Cake. Mr. and Mrs. Short who were landlords of the White Hart let me use the room with the piano in so we had a great evening. The £21.00 was put behind the bar and I don’t remember going to bed that night.

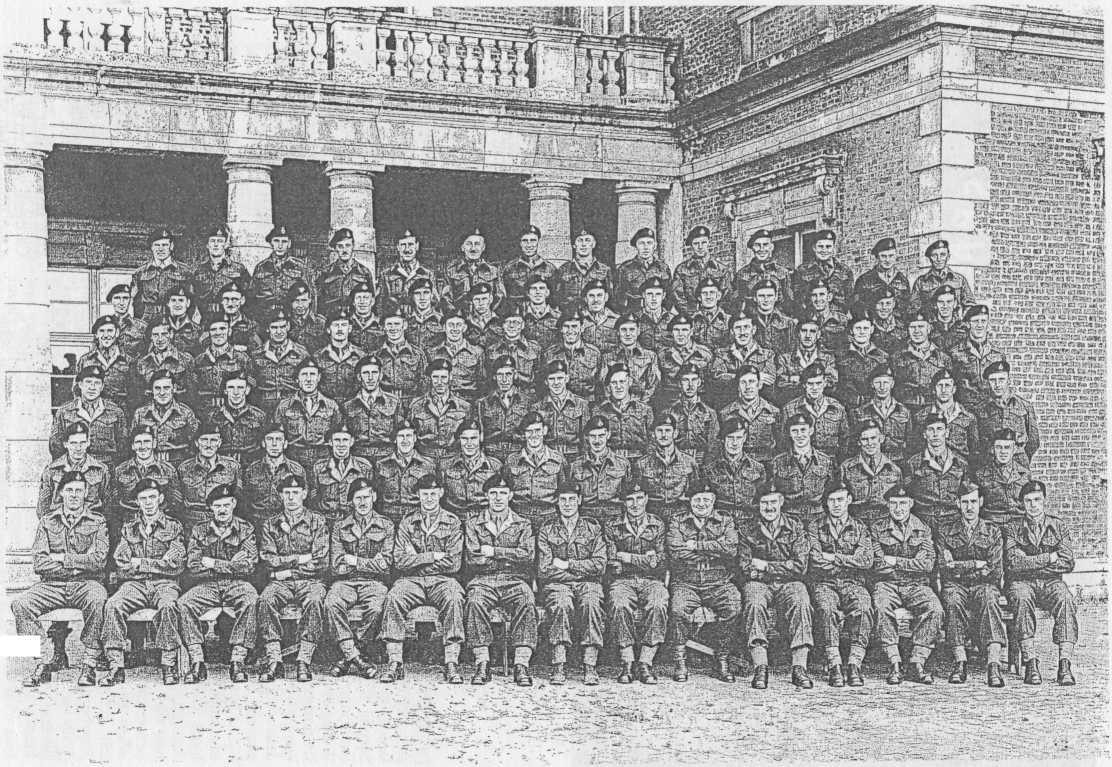

This was 1941 and what was left of the 8th Northumberland Fusiliers was made up to strength with volunteers from other regiments. We then, in 1941, formed the 3rd Recce Regt. (NF) 3rd British Division and started strict training. We had A.B & C Squadrons at Shillingstone, Durweston and Child Okeford, Headquarters being at Sturminster Newton.

We then did lots of training on Salisbury Plain. Our next move was to Cornwall. I went to Prah Sands. We had machine gun posts on The Lizard and we helped with beach defences preparing for German invasion.

We moved to Berkhampstead in 1942. It was then that I received a telegram from home saying that Mother was very ill and I should come home. As it was a Sunday only one Duty Officer and the Guard were present. The Officer could only give me a pass for 48 hours and no money. I grabbed the pass and headed for London. I went on to the platform at Kings Cross and was about to climb on the train when two Military Police asked to see my pass.

I showed my pass but they said I had to see the Provost Marshal. I asked them if I could go to the toilet first, so I went down the steps and was about halfway down when I turned quick, hit one man and kicked the other then dashed on to the platform and boarded the train for Newcastle. I stayed in the toilet until I got to York and then walked up and down the corridor and smoked fags. I arrived home and saw Mother. She died in the night and I had to ask for more leave.

I was given another 36 hours but could only attend the funeral and had to catch the next train back. This I did but was still late arriving at my Station and was charged with being AWOL.

I felt that the world was against me but was fortunate that we had a very good Commanding Officer, Lt. Col. Merriman M.C. He said that the Duty Sgt. had just done his job and that he was sorry that I had lost my mother and the charge was dropped.

I had a chip on my shoulder and was determined to do something with my life. A course came up for a Staff Sgt. (Technical MT). None of our Sgts, wanted the course, so I was allowed to go to Chilwell for two weeks. I passed with an ‘A’. I was not allowed to take the rank but was given trade pay, bringing my pay to 4/6d per day as a Tech. CpI.

This was 1941 and what was left of the 8th Northumberland Fusiliers was made up to strength with volunteers from other regiments. We then, in 1941, formed the 3rd Recce Regt. (NF) 3rd British Division and started strict training. We had A.B & C Squadrons at Shillingstone, Durweston and Child Okeford, Headquarters being at Sturminster Newton.

We then did lots of training on Salisbury Plain. Our next move was to Cornwall. I went to Prah Sands. We had machine gun posts on The Lizard and we helped with beach defences preparing for German invasion.

We moved to Berkhampstead in 1942. It was then that I received a telegram from home saying that Mother was very ill and I should come home. As it was a Sunday only one Duty Officer and the Guard were present. The Officer could only give me a pass for 48 hours and no money. I grabbed the pass and headed for London. I went on to the platform at Kings Cross and was about to climb on the train when two Military Police asked to see my pass.

I showed my pass but they said I had to see the Provost Marshal. I asked them if I could go to the toilet first, so I went down the steps and was about halfway down when I turned quick, hit one man and kicked the other then dashed on to the platform and boarded the train for Newcastle. I stayed in the toilet until I got to York and then walked up and down the corridor and smoked fags. I arrived home and saw Mother. She died in the night and I had to ask for more leave.

I was given another 36 hours but could only attend the funeral and had to catch the next train back. This I did but was still late arriving at my Station and was charged with being AWOL.

I felt that the world was against me but was fortunate that we had a very good Commanding Officer, Lt. Col. Merriman M.C. He said that the Duty Sgt. had just done his job and that he was sorry that I had lost my mother and the charge was dropped.

I had a chip on my shoulder and was determined to do something with my life. A course came up for a Staff Sgt. (Technical MT). None of our Sgts, wanted the course, so I was allowed to go to Chilwell for two weeks. I passed with an ‘A’. I was not allowed to take the rank but was given trade pay, bringing my pay to 4/6d per day as a Tech. CpI.

Dedicated to: 3rd Recce Regt(NF)

MONTY’S MOONLIGHT

You’ve been chosen for patrol

It brings fear into your soul

When you move into the night

To observe, but not to fight.

You can see the Boch right there

But you mustn’t move a hair

Or he’ll spot you in his sights

And then put out your lights.

But you move another yard

Holding back is very hard

And your message back to base

Is a job that they must face.

Be it infantry or tank

You must always be quite frank

‘tis no use to send platoon

When you really need ‘Typhoon’.

They are the boys to beat the tigers

Armoured cars cannot compete

But their rockets hi/- the tigers

And their tanks are incomplete.

Another night is over, and a job we hope, well done

But the sun comes in the morning, and the shelling by the Hun

No respite has he given us, once more we’re on our guard

No rest, no sleep, we find it very, very hard

No fire, no home, to greet us in the mom’

But we have all our comrades, and they will keep us warm.

We’ve done our job, good time well spent

We are “The Recce regiment”

Relax, stand down, and have no fears

You’re with Northumberland Fusiliers.

MONTY’S MOONLIGHT

You’ve been chosen for patrol

It brings fear into your soul

When you move into the night

To observe, but not to fight.

You can see the Boch right there

But you mustn’t move a hair

Or he’ll spot you in his sights

And then put out your lights.

But you move another yard

Holding back is very hard

And your message back to base

Is a job that they must face.

Be it infantry or tank

You must always be quite frank

‘tis no use to send platoon

When you really need ‘Typhoon’.

They are the boys to beat the tigers

Armoured cars cannot compete

But their rockets hi/- the tigers

And their tanks are incomplete.

Another night is over, and a job we hope, well done

But the sun comes in the morning, and the shelling by the Hun

No respite has he given us, once more we’re on our guard

No rest, no sleep, we find it very, very hard

No fire, no home, to greet us in the mom’

But we have all our comrades, and they will keep us warm.

We’ve done our job, good time well spent

We are “The Recce regiment”

Relax, stand down, and have no fears

You’re with Northumberland Fusiliers.

DUNKIRK and D-Day are probably the two most famous events of the Second World War and .Stalbridge pensioner Ernie Wilson is a veteran of both. Ex-postman Ernie is best known for his 18 years of delivering letters- around the peaceful Blackmore Vale but he has vivid memories of events which were vastly more dramatic.

Amazingly, his military destiny was decided on the toss of a coin. This was in 1939, when the young Ernie was Still living in his native Newbum, Northumberland. With war imminent, he and his best buddy John Tait - known as Johnty - vowed that whatever they did, they would do it together.

"I wanted to join the Navy, as it was clean with no square bashing, carrying packs etc. Johnty wanted to join the Army, so we spun the coin and he won." They duly appeared at Newburn Drill Hall, where Ernie passed.his medical and waited for his friend. "When he came out, he had failed his medical, so I was -on my own."

A few months later, Ernie was on his way to France with a motor cycle battalion Of the Northumberland Fusiliers.

When we landed at -Cherbourg, we were as green as grass," he admits. "Our biggest weapon - a 2 lbs Boys anti-tank rifle - was no match for Hitler's tanks and armoured vehicles."

The Northumberland's arrived in-Belgium just in time to learn of the Belgian surrender.

So we had to make a speedy withdrawal back, to Arras'in France or be taken prisoner.

Arras had been heavily . bombed and a huge crater was in tire centre of the town.

No vehicles could come in and those which were in could not get out, except of course the Northumberland Fusiliers, who could ride motor cycles and sidecars. We used to lift the sidecars and ride on two wheels." Ernie, of Blackmore Road, Stalbridge, goes on: "These were tough days - no food, no water and nothing to fight with.

A sergeant known as 'Snakey' Cardwell earned a German machine gun and would sit on the roof of dur billet. We passed ammunition through the skylight. "He used to shout at the Genies: 'I am too wicked to kill.' He was awarded the Military Medal." Like Ernie himself, Sgt Cardwell went on to many a girl from Hinton St Mary.

Amazingly, his military destiny was decided on the toss of a coin. This was in 1939, when the young Ernie was Still living in his native Newbum, Northumberland. With war imminent, he and his best buddy John Tait - known as Johnty - vowed that whatever they did, they would do it together.

"I wanted to join the Navy, as it was clean with no square bashing, carrying packs etc. Johnty wanted to join the Army, so we spun the coin and he won." They duly appeared at Newburn Drill Hall, where Ernie passed.his medical and waited for his friend. "When he came out, he had failed his medical, so I was -on my own."

A few months later, Ernie was on his way to France with a motor cycle battalion Of the Northumberland Fusiliers.

When we landed at -Cherbourg, we were as green as grass," he admits. "Our biggest weapon - a 2 lbs Boys anti-tank rifle - was no match for Hitler's tanks and armoured vehicles."

The Northumberland's arrived in-Belgium just in time to learn of the Belgian surrender.

So we had to make a speedy withdrawal back, to Arras'in France or be taken prisoner.

Arras had been heavily . bombed and a huge crater was in tire centre of the town.

No vehicles could come in and those which were in could not get out, except of course the Northumberland Fusiliers, who could ride motor cycles and sidecars. We used to lift the sidecars and ride on two wheels." Ernie, of Blackmore Road, Stalbridge, goes on: "These were tough days - no food, no water and nothing to fight with.

A sergeant known as 'Snakey' Cardwell earned a German machine gun and would sit on the roof of dur billet. We passed ammunition through the skylight. "He used to shout at the Genies: 'I am too wicked to kill.' He was awarded the Military Medal." Like Ernie himself, Sgt Cardwell went on to many a girl from Hinton St Mary.

After blowing up all their ammunition and belongings, the Northumberland's were finally relieved at Arras by the Welsh Fusiliers in what Ernie describes as "the only bayonet charge I have ever seen".

He recalls: "We crept out at dawn on a foggy morning after a gap had been made. We were very wet and very hungry.

"I was with an old soldier, RQMS Bob Cowans. He told me to stay with him and I would be all right.' "I clung to him like a leech! We made our way to Dunkirk but that was only after running, hiding, taking cover and pushing along with the refugees. No-one knew who was which." Ernie, who'll be 81 on Tuesday, finally arrived at Dunkirk on May 29, 1940 - his 20th birthday.

He remembers five col- leagues celebrating their imminent evacuation by opening a tin of sardines and a packet of hard-tack biscuits.

But the celebration was a touch premature. Ernie recalls: "It was terrible. We thought we would be taken off the beach straight away but it was not to be as thousands had arrived before iis. "We took cover from the Stukas as best we could and carried stretchers on to the hospital ships moored at the broken pier, which had been bombed in two places. "Planks were placed over the gaps and we swayed as we walked over them with the wounded.

"One hero, Sgt French, had his leg blown off quite near us. As we carried him on board, one of the sailors threw me a tin of fruit, or so I thought. I looked forward to sharing it with my friends to celebrate my birthday. "Five of us found a place of safety under the cliffs and : shared a packet of hard-tack and my tin of fruit - which turned out to be a tin of peas!, "We were glad of the water as we had not had food or drink for seven days. Nothing was left of the peas."

After a cold and sleepless night, punctuated by exploding bombs and machine gun fire, dawn arrived to present a new tragedy to Ernie and his friends. ."We could see what appeared to be fluorescent soldiers lying on the beach glowing in the semi-darkness.

"A bomb had scored a direct down the funnel of the ship which was to have taken the Guards to safety and home." After another day of Stuka dodging, the lads.finally made it on to HMS Vimy and were soon heading for Pembroke Docks.

By this time Ernie's distraught mother believed that her son had been killed in action and her daughter Annie had gone down with the Cairn Ross oh her way back from Canada.

"She couldn't believe it when she got my telegram saying I was on my way home," says Ernie.

"The man killed in action turned out to be a Robert Wilson who lived half-a- mile from me and Was also a Northumberland. Fusilier." When Ernie reached Newburn in the early hours, it was Annie who opened the door - she had taken a later ship and arrived just hours before him!

Ernie's next destination was a far cry from Dunkirk and Northumberland.

"I had no idea where Sturminster Newton was but was very pleased to find a lovely village.

"I was billeted at Hinton St".

He recalls: "We crept out at dawn on a foggy morning after a gap had been made. We were very wet and very hungry.

"I was with an old soldier, RQMS Bob Cowans. He told me to stay with him and I would be all right.' "I clung to him like a leech! We made our way to Dunkirk but that was only after running, hiding, taking cover and pushing along with the refugees. No-one knew who was which." Ernie, who'll be 81 on Tuesday, finally arrived at Dunkirk on May 29, 1940 - his 20th birthday.

He remembers five col- leagues celebrating their imminent evacuation by opening a tin of sardines and a packet of hard-tack biscuits.

But the celebration was a touch premature. Ernie recalls: "It was terrible. We thought we would be taken off the beach straight away but it was not to be as thousands had arrived before iis. "We took cover from the Stukas as best we could and carried stretchers on to the hospital ships moored at the broken pier, which had been bombed in two places. "Planks were placed over the gaps and we swayed as we walked over them with the wounded.

"One hero, Sgt French, had his leg blown off quite near us. As we carried him on board, one of the sailors threw me a tin of fruit, or so I thought. I looked forward to sharing it with my friends to celebrate my birthday. "Five of us found a place of safety under the cliffs and : shared a packet of hard-tack and my tin of fruit - which turned out to be a tin of peas!, "We were glad of the water as we had not had food or drink for seven days. Nothing was left of the peas."

After a cold and sleepless night, punctuated by exploding bombs and machine gun fire, dawn arrived to present a new tragedy to Ernie and his friends. ."We could see what appeared to be fluorescent soldiers lying on the beach glowing in the semi-darkness.

"A bomb had scored a direct down the funnel of the ship which was to have taken the Guards to safety and home." After another day of Stuka dodging, the lads.finally made it on to HMS Vimy and were soon heading for Pembroke Docks.

By this time Ernie's distraught mother believed that her son had been killed in action and her daughter Annie had gone down with the Cairn Ross oh her way back from Canada.

"She couldn't believe it when she got my telegram saying I was on my way home," says Ernie.

"The man killed in action turned out to be a Robert Wilson who lived half-a- mile from me and Was also a Northumberland. Fusilier." When Ernie reached Newburn in the early hours, it was Annie who opened the door - she had taken a later ship and arrived just hours before him!

Ernie's next destination was a far cry from Dunkirk and Northumberland.

"I had no idea where Sturminster Newton was but was very pleased to find a lovely village.

"I was billeted at Hinton St".

We then moved to Scotland, I was stationed in Dufftown and the Squadron were moved to Cullen to do Commando Training in preparation for D Day. This is a very rough coast at the North of Scotland. Our training was very tough but made us very fit. On completing our training we moved down to Fort William where we were inspected by King George VI and General Montgomery who told us that we were privileged to land on D Day. We then came to Aidershot to waterproof our vehicles and we were ready to sail from Tilbury Docks to land on ‘Sword Beach’. The first man on the Sword Beach with a troop of Royal Engineers to pick up the mines was a friend of mine A/Sgt. Harry Me Carten 4273467, he received the ‘Croix de Guerre’. He remained on duty for 48 hours without relief under continuous fire from shellfire and bombing.

On ‘D - Day’ the Contact Detachments and the Beach Traffic Control Group landed with the assaulting troops under the Command respectively of Major Gaskell and Major Gill. Frequently we were under heavy fire, clearing the very congested beaches of vehicles and moving to forward positions. Unfortunately Major Gill was severely wounded and was returned to England. During this time wireless links were made to all groups and I think we had our first casualty when Monty Morton, our wireless operator, had to come out of his trench because of the noise of gun-fire. HMS Rodney was firing 16-inch shells over our heads and our Lancaster and Halifax bombers were bombing caen continuously.

This was completely successful and Tebissey was captured by 185 Brigade commanded by Brigadier Bols. Progress was slowly but steadily being made, and we were held responsible for the left flank of the Division. Mine fields and booby traps made for slow progress but we made contact with the Americans and moved up into Holland. Our job was to keep the bren carriers and armoured cars supplied with petrol, oil and lubricants. We were moving faster now and the vehicles were only doing about six miles to the gallon as they were moving forward.

Technical Sgt. John Kelly and I went back to the supply depot with a 3-ton lorry and a German trailer each to fetch more petrol. I was behind him and waited under the trees until he was loaded but, unfortunately Jerry came over bombing and my driver and I took cover behind a wall. When we looked up Sgt. Kelly and his load had been hit and was just a mass of flames. We loaded our vehicle as fast as possible and returned to our unit very shocked.

The winter was now upon us, and we were sleeping in our trenches when possible. The tracked vehicles were frozen to the ground and we waited for our “Rum Ration’’ at four o’clock when we had the signal to “Splice the Mainbrace”. We could see the Germans on the other side of the River Maas and we were hoping to give the children in the village a treat for Christmas. However we were called out to do a “Recce” for the Americans. We were now taking lots of prisoners as we were moving forward and entered into Munster. The Americans took over from here and we went on to finish our job by reaching as far as Bremen and, for us, that was the end of the fighting and the war.

The war was over and most of our Regiment were demobbed. I stayed on to hand our vehicles over to the 15/19 Hussars. I was then T.Q.M.S. but was then transferred to 10lh Royal Hussars. After being ill in hospital for two weeks and then demobbed I came home for a long leave and recuperation.

On ‘D - Day’ the Contact Detachments and the Beach Traffic Control Group landed with the assaulting troops under the Command respectively of Major Gaskell and Major Gill. Frequently we were under heavy fire, clearing the very congested beaches of vehicles and moving to forward positions. Unfortunately Major Gill was severely wounded and was returned to England. During this time wireless links were made to all groups and I think we had our first casualty when Monty Morton, our wireless operator, had to come out of his trench because of the noise of gun-fire. HMS Rodney was firing 16-inch shells over our heads and our Lancaster and Halifax bombers were bombing caen continuously.

This was completely successful and Tebissey was captured by 185 Brigade commanded by Brigadier Bols. Progress was slowly but steadily being made, and we were held responsible for the left flank of the Division. Mine fields and booby traps made for slow progress but we made contact with the Americans and moved up into Holland. Our job was to keep the bren carriers and armoured cars supplied with petrol, oil and lubricants. We were moving faster now and the vehicles were only doing about six miles to the gallon as they were moving forward.

Technical Sgt. John Kelly and I went back to the supply depot with a 3-ton lorry and a German trailer each to fetch more petrol. I was behind him and waited under the trees until he was loaded but, unfortunately Jerry came over bombing and my driver and I took cover behind a wall. When we looked up Sgt. Kelly and his load had been hit and was just a mass of flames. We loaded our vehicle as fast as possible and returned to our unit very shocked.

The winter was now upon us, and we were sleeping in our trenches when possible. The tracked vehicles were frozen to the ground and we waited for our “Rum Ration’’ at four o’clock when we had the signal to “Splice the Mainbrace”. We could see the Germans on the other side of the River Maas and we were hoping to give the children in the village a treat for Christmas. However we were called out to do a “Recce” for the Americans. We were now taking lots of prisoners as we were moving forward and entered into Munster. The Americans took over from here and we went on to finish our job by reaching as far as Bremen and, for us, that was the end of the fighting and the war.

The war was over and most of our Regiment were demobbed. I stayed on to hand our vehicles over to the 15/19 Hussars. I was then T.Q.M.S. but was then transferred to 10lh Royal Hussars. After being ill in hospital for two weeks and then demobbed I came home for a long leave and recuperation.

Chapter Four

Civvie Street.

Fully recovered, I went back to Sturminster Newton to be married to Nora Innes at Hinton St. Mary on 1st June 1946.

We went to Babbacombe for our honeymoon and then home to Newburn. We put our names down for a house but there was no hope. I went back to my job at Todd Bros in Newcastle and collected my first pay of £4.10s.od, I asked my boss about pay as I was now married, but he said that I had not finished my apprenticeship and was just a shop assistant.

Our daughter Susan was born on 29th August 1947, we were then living in two rooms with my sister and her husband. That winter up North was terrible, we had 20ft snowdrifts and roads were blocked. Nora was ill and had to have the doctor. He said she could not stand the cold and suggested we move to a warmer climate. I said she was born in Dorset so I will take her back to Dorset.

We came back to Dorset in 1948 and I got work with Cyril Dike in his grocer’s shop. We lived with Nora’s mother at Hinton St Mary and I cycled to work each day to Stalbridge. We applied for a Council House at the Council Offices at Sturminster Newton. Later we were offered a Nissen Hut at Priors Down in Stalbridge, which we accepted. We were there for twelve months before we were offered a Council House at 4 Park Grove, Stalbridge. This was wonderful, a big garden which was then a field, but after a lot of hard work we had a lovely garden and of course right opposite the playing field. Anthony, our son was born on 14th December 1951.

Cyril Dike and I were both crazy on football. We both played for Stalbridge and had a season ticket for Southampton. We went to all the home games. Cyril also introduced me to the Royal British Legion as he had also served in H.M. Forces in Greece.

I devoted most of my spare time to the R.B.L. serving on most of the Committees. I took part in the five mile run around the Park Wail when I was 65, this run was for the Guide Dogs for the Blind and the Roof Repair fund. We started the 200 Club for the Service Committee and helped many ex - servicemen during the years. I worked at Dikes for ten years and then worked for Marglass as a weaver for only one year, permanent night - shift. This was terrible working in the heat. I needed the money but then I also needed fresh air. I applied to the Post Office in Sturminster Newton for the job of postman.

Civvie Street.

Fully recovered, I went back to Sturminster Newton to be married to Nora Innes at Hinton St. Mary on 1st June 1946.

We went to Babbacombe for our honeymoon and then home to Newburn. We put our names down for a house but there was no hope. I went back to my job at Todd Bros in Newcastle and collected my first pay of £4.10s.od, I asked my boss about pay as I was now married, but he said that I had not finished my apprenticeship and was just a shop assistant.

Our daughter Susan was born on 29th August 1947, we were then living in two rooms with my sister and her husband. That winter up North was terrible, we had 20ft snowdrifts and roads were blocked. Nora was ill and had to have the doctor. He said she could not stand the cold and suggested we move to a warmer climate. I said she was born in Dorset so I will take her back to Dorset.

We came back to Dorset in 1948 and I got work with Cyril Dike in his grocer’s shop. We lived with Nora’s mother at Hinton St Mary and I cycled to work each day to Stalbridge. We applied for a Council House at the Council Offices at Sturminster Newton. Later we were offered a Nissen Hut at Priors Down in Stalbridge, which we accepted. We were there for twelve months before we were offered a Council House at 4 Park Grove, Stalbridge. This was wonderful, a big garden which was then a field, but after a lot of hard work we had a lovely garden and of course right opposite the playing field. Anthony, our son was born on 14th December 1951.

Cyril Dike and I were both crazy on football. We both played for Stalbridge and had a season ticket for Southampton. We went to all the home games. Cyril also introduced me to the Royal British Legion as he had also served in H.M. Forces in Greece.

I devoted most of my spare time to the R.B.L. serving on most of the Committees. I took part in the five mile run around the Park Wail when I was 65, this run was for the Guide Dogs for the Blind and the Roof Repair fund. We started the 200 Club for the Service Committee and helped many ex - servicemen during the years. I worked at Dikes for ten years and then worked for Marglass as a weaver for only one year, permanent night - shift. This was terrible working in the heat. I needed the money but then I also needed fresh air. I applied to the Post Office in Sturminster Newton for the job of postman.

GARDENERS WORLD

If your garden isn’t up to scratch

And your sprouts look poor in your cabbage patch

Then talk to the experts in the region

And call at “Stalbridge British Legion”

The time is Sunday twelve-to-one

So while the wife puts your dinner on

Just take a walk don’t take your car

Because the Legion has a bar

Now “Wig” will always take the chair

And “Scanny” will be sitting there

Talking of his giant marrow

Which he brought up in his wheel-barrow

Then “Ben” comes in with a runner-bean

The longest one you’ve ever seen

But George thinks that the one is two

And he has stack them up with glue

The talking starts just like a parrot

And “Wiggy” tells them of his carrot

The one he grew would feed a mule

He measured it with a three foot rule

Now if you want a Trench ask George

He’ll dig you one like Cheddar Gorge

It’s thirsty work from start to finish

So just buy him another Guinness

Don’t forget to come next week

And “Ernie” will explain the leek

It is the longest reared by hand

From his beloved “Geordie-Land

We need your help that is the reason

Why you should join the “British Legion”.

If your garden isn’t up to scratch

And your sprouts look poor in your cabbage patch

Then talk to the experts in the region

And call at “Stalbridge British Legion”

The time is Sunday twelve-to-one

So while the wife puts your dinner on

Just take a walk don’t take your car

Because the Legion has a bar

Now “Wig” will always take the chair

And “Scanny” will be sitting there

Talking of his giant marrow

Which he brought up in his wheel-barrow

Then “Ben” comes in with a runner-bean

The longest one you’ve ever seen

But George thinks that the one is two

And he has stack them up with glue

The talking starts just like a parrot

And “Wiggy” tells them of his carrot

The one he grew would feed a mule

He measured it with a three foot rule

Now if you want a Trench ask George

He’ll dig you one like Cheddar Gorge

It’s thirsty work from start to finish

So just buy him another Guinness

Don’t forget to come next week

And “Ernie” will explain the leek

It is the longest reared by hand

From his beloved “Geordie-Land

We need your help that is the reason

Why you should join the “British Legion”.

Legion on parade at Stalbridge

For the first time In living memory in Stalbridge, on Sunday morning a band marched in procession through the High Street.

To celebrate their diamond Jubilee, men and women of the Stalbridge Branch of the Royal British Legion paraded from the Village Hall to St. Mary's Church. led by the Gillingham town Band.

The parade was taken by Mr. E. K. Wilson.. a former Warrant Officer in the 3rd Reconnaissance Regiment. Northumberland Fusiliers, and included standard bearers and escorts from Stalbridge. Marnhull. Milborne Port and Mere Branches, members of the R.O.A.B. and Stalbridge Scouts, Cub Scouts. Girl Guides and Brownies and the Youth Club — about 120 people In all.

A full congregation took part In the service in St. Mary's Church conducted by the Rev. F. W. Pugh, branch chaplain? In his address, the Rector spoke of the work of the Legion.

The Exhortation and lesson were read by Lt. Col. E. C. T. Wilson. V.C., and prayers were read by Mr. P. Lewis, Mr. R. Mansfield and Mr. J. Smith.

Pro-reeds from me collection will be donated to the Earl Haig Poppy Fund.

To celebrate their diamond Jubilee, men and women of the Stalbridge Branch of the Royal British Legion paraded from the Village Hall to St. Mary's Church. led by the Gillingham town Band.

The parade was taken by Mr. E. K. Wilson.. a former Warrant Officer in the 3rd Reconnaissance Regiment. Northumberland Fusiliers, and included standard bearers and escorts from Stalbridge. Marnhull. Milborne Port and Mere Branches, members of the R.O.A.B. and Stalbridge Scouts, Cub Scouts. Girl Guides and Brownies and the Youth Club — about 120 people In all.

A full congregation took part In the service in St. Mary's Church conducted by the Rev. F. W. Pugh, branch chaplain? In his address, the Rector spoke of the work of the Legion.

The Exhortation and lesson were read by Lt. Col. E. C. T. Wilson. V.C., and prayers were read by Mr. P. Lewis, Mr. R. Mansfield and Mr. J. Smith.

Pro-reeds from me collection will be donated to the Earl Haig Poppy Fund.

I passed the exam and started as relief postman for seven years, learning all the rounds, I loved this job and stayed there for 18 years before retiring.

We lived in the house at Park Grove for 45 years, we had a mortgage and bought the house. Eventually, Nora was ill and couldn't walk up stairs and the garden was getting too much for me to manage, so we sold the house and bought a bungalow in Stalbridge and still live there now, in Westacres.

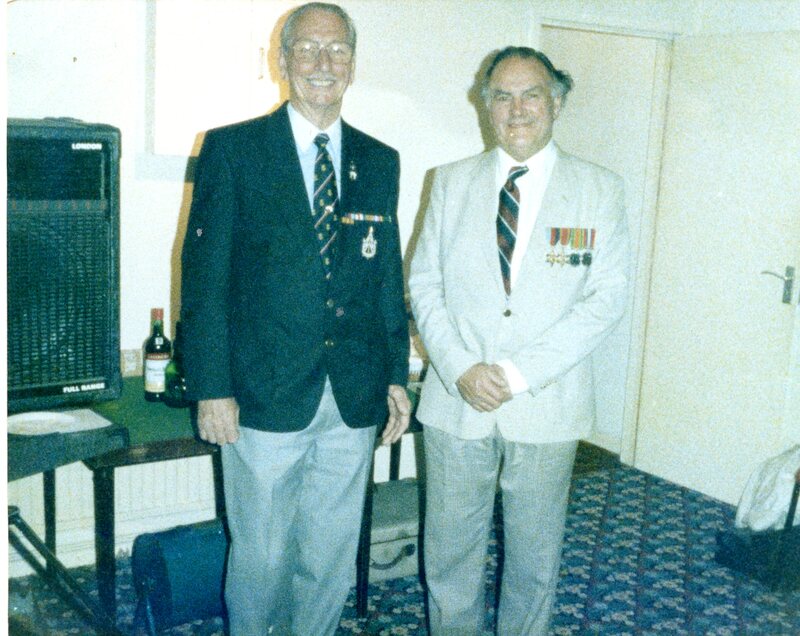

In 1994 I was fortunate enough to win the G.P.O. Competition to go back to the Normandy Beaches for the D Day Fiftieth Anniversary Celebrations, along with Len Beddow, a soldier who also won the competition and served with the 24th Lancers. He also served in France, Belgium, Holland and Germany.

We were flown out to Normandy and our first visit was to “The Chateau L’lsle Marie” where we were greeted with a champagne reception and lunch, before being taken out to the beaches.

Despite the attentions of photographers and onlookers, we did not forget the reason we were there, to remember our fallen comrades. And looking at the bleak, open beaches and the remains of the German defences, we wondered how anyone had got across it, when it was raked with machine gun and mortar fire from the defence positions. It must have been a miracle.

I have now been a member of Stalbridge Royal British Legion for over 50 years but most of my friends and comrades have gone. It isn’t like a Royal British Legion now. To me, aged 81, its more like a Youth Club.

Members of 3rd Recce Regt. (NF) who married Dorset girls or evacuees living in Dorest:

Jack Bell

Paddy Byms

Sandy Campbell

Arthur Cardwell

Fred Willis

Ernie Wilson

Published by J. C. Coulson, Wylan-on-Tyne 2002

We lived in the house at Park Grove for 45 years, we had a mortgage and bought the house. Eventually, Nora was ill and couldn't walk up stairs and the garden was getting too much for me to manage, so we sold the house and bought a bungalow in Stalbridge and still live there now, in Westacres.

In 1994 I was fortunate enough to win the G.P.O. Competition to go back to the Normandy Beaches for the D Day Fiftieth Anniversary Celebrations, along with Len Beddow, a soldier who also won the competition and served with the 24th Lancers. He also served in France, Belgium, Holland and Germany.

We were flown out to Normandy and our first visit was to “The Chateau L’lsle Marie” where we were greeted with a champagne reception and lunch, before being taken out to the beaches.

Despite the attentions of photographers and onlookers, we did not forget the reason we were there, to remember our fallen comrades. And looking at the bleak, open beaches and the remains of the German defences, we wondered how anyone had got across it, when it was raked with machine gun and mortar fire from the defence positions. It must have been a miracle.

I have now been a member of Stalbridge Royal British Legion for over 50 years but most of my friends and comrades have gone. It isn’t like a Royal British Legion now. To me, aged 81, its more like a Youth Club.

Members of 3rd Recce Regt. (NF) who married Dorset girls or evacuees living in Dorest:

Jack Bell

Paddy Byms

Sandy Campbell

Arthur Cardwell

Fred Willis

Ernie Wilson

Published by J. C. Coulson, Wylan-on-Tyne 2002

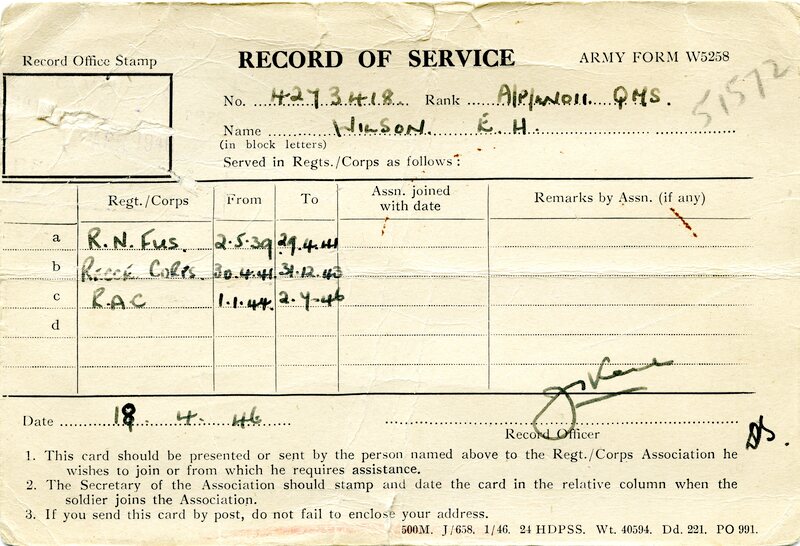

Content added by Ian Semple September 2021

Ernie Wilson Medals L to R

1 The 1939–1945 Star is a military campaign medal instituted in 1943 to award to subjects of the British Commonwealth for service in WW2.

2 The France and Germany Star

3 The defence Medal

4 The War Medal 1939–1945

5 Efficiency Medal Territorial 1939

6 The Dunkirk Medal (Medaille Dunkerque 1940)

7 The Normandy Campaign Medal

8 he Medal of a liberated France "Médaille de la France libérée"

Credits..

Ernie Wilson, Roger Guttridge and Tony Wilson (Ernie's son)

Ian Semple September 2021